Most analyses of China’s One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative tend to focus on two core aspects of President Xi Jinping’s ambitious vision of a more interconnected Europe, Asia and Africa: the political motivations behind it, and whether the economic realities even render Beijing’s plans for a modern Silk Road feasible. While the political focus tends to be on Beijing looking eastward for alliances in the wake of an increasing post-pivot US presence and the recent conclusion of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (which includes the US, but not China), economic conditions in China are increasing the urgency and necessity of new opportunities to put its vast manufacturing powers to use. But despite the many criticisms and concerns over China’s political objectives and whether or not OBOR will realize its full potential, this initiative has already begun to alter the Eurasian economic and business landscape through its creation of financial capital, pushing of economic and legal reforms, and increased institutionalization of the region.

Filling the financial gap

At the heart of OBOR is the need for China to create new avenues for increasing outbound investment in order to assist in maintaining strong economic growth as it transitions to the more sustainable and high-quality economy outlined in Xi’s concept of a “new normal.” As such, one of the major regional problems that OBOR will contribute to remedying is the massive shortage of available funding for infrastructure investment in the region. This became abundantly clear in 2009, when the Asian Development Bank (ADB) released a report estimating that Asia will suffer as much as an $8 trillion gap in infrastructure investment for the decade of 2010-2020. Given that the World Bank and ADB combined provide only around $20 billion per year to Asia, it’s no surprise that emerging economies in the region are seeking new avenues to address this issue.

China’s most significant move toward addressing this shortage has been its central role in creating the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). Though not officially associated with OBOR, the new investment bank was announced by Xi the month after his unveiling of the New Silk Road Economic Belt, and one of its primary objectives is to fund connectivity throughout Asia, which goes hand in hand with OBOR’s goals. Additionally, China has created a $40 billion Silk Road Fund, and earlier this year the State Council directed China’s three policy banks to strengthen their commitment to pursuing government policies and strategic agendas, including plans for infrastructure investment that falls in line with OBOR’s objectives.

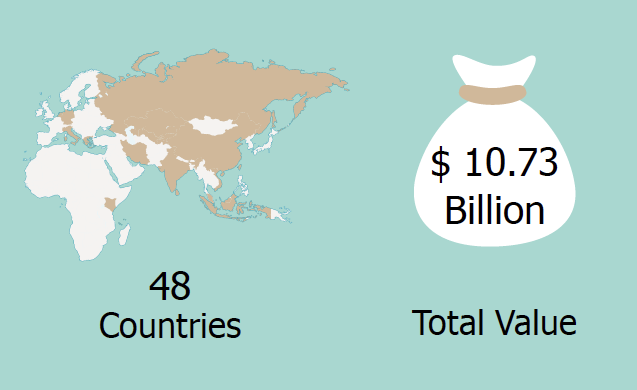

Regardless of whether or not OBOR achieves its goals, it is clear that since Xi’s announcement of the Silk Road as a major feature of China’s foreign and economic policies, much-needed financial capital is now put to use to improve the infrastructure gap. Demonstrating this fact, the first eight months of 2015 have seen a 48.2 percent increase in Chinese foreign direct investment to OBOR countries, giving a clear indication that China is serious about its pursuit of the New Silk Road, and that to some degree this is resulting in better infrastructure and connectivity throughout the region, which will lead to new business opportunities and minimize costs for those who can take advantage of this emerging infrastructure environment.

Improving regulatory frameworks

Though maybe not as fundamental to OBOR as the push for infrastructure, another promising aspect of the New Silk Road’s creation is the expansion of institutional cohesion throughout the region. According to AmCham China’s 2015 White Paper, rule of law is the No. 1 area where AmCham members seek reform. China’s Vision and Actions on Jointly Building the Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road, released in March, calls for adherence to international norms, increased bilateral and multilateral congruence, and the protection of investors’ lawful rights.

Along with the Silk Road Vision, Beijing also launched a series of legal reforms aimed at assisting and complementing the new trade routes. Among these were notable documents released by the State Administration of Taxation and the General Administration of Customs announcing reforms intended to facilitate smoother trade along the OBOR network. The customs reform seeks first to create an integrated customs clearance system among the 10 initial cities associated with it, spanning from the port of Qingdao to Xinjiang and Tibet, so that goods entering any of these cities only require one customs declaration to travel among any of them, thus cutting down on storage time due to bureaucratic delays. This integrated clearance system is planned to expand to 42 customs offices throughout China as OBOR continues to grow.

Regarding taxation, the State Administration of Taxation announced a variety of tax measures to accompany OBOR and protect those doing business on the New Silk Road. These measures are aimed at avoiding double taxation, avoiding tax losses and establishing special channels with partner countries to deal with tax disputes, and they are being pursued via bilateral tax agreements with OBOR participants.

In addition to such domestic reforms and bilateral agreements, China is expanding its multilateral ties throughout the region to assist in the realization of OBOR. Earlier this year, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (an international, intergovernmental organization) expanded its membership to include India and Pakistan as full members, and Armenia, Azerbaijan, Cambodia and Nepal as observer nations. The organization overlaps significantly with the Russian-led Eurasian Economic Union, which operates similarly to the European Union, acting as a single market and strengthening legal and regulatory relations among member countries. As the Shanghai Cooperation Organization becomes increasingly intertwined with the Eurasian Economic Union, it will be in Beijing’s interest not only to adopt existing laws governing trade in the region, but to also act as a leader in pushing for new and stronger reforms to protect its growing interests in the region. As more formal institutions continue to be created and expanded, these new links will exert pressure on China to establish uniform rules and regulations with OBOR partners as well as strengthen its dedication to a strong and consistent rule of law – all of which will lend to a more stable and coherent business environment in China and the region.

The shape of things to come

Taken together, these three elements – increased access to financial resources, new legal reforms and a deepening institutionalization of the region – establish a more expansive and coherent regulatory framework in the region. OBOR is making significant changes to China and the Eurasian region as a whole. As demonstrated by actions such as the creation of the Silk Road Fund and the AIIB, along with the new direction of China’s policy banks and ever-expanding political and institutional ties throughout the region, it is clear Beijing is dedicated to realizing the vision of the initiative. While serious questions remain over how successful these plans will actually be, as well as the degree to which OBOR can assist in propping up China’s slowing economy, it is clear that a significant amount of financial capital and institutional development is being dedicated to it. Even if OBOR fails to live up to expectations, it will nonetheless leave in its wake a more developed region with a stronger and more coherent legal framework – all of which will bring about new opportunities and a better environment for doing business.