By Arendse Huld

As the pending CPC nears, we look at the China’s previous Party Congress in 2017, which laid out a policy agenda for the country’s growth and development and set key targets for the next half-century. We look back at some of the major events that have occurred over the last five years and discuss economic and industry growth, regulatory developments, and the policy trajectories that have taken the country into the 2020s.

China has witnessed rapid economic growth and major changes to its regulatory and policy environment in the last five years. The steady development of technology and other emerging industries along with the targeted development policies and improved standards and regulations continue to see the country on its way to becoming an advanced, high-income economy.

In the run-up to the start of the 20th Party Congress on October 16, the most important political congress in China, we take a look at the major developments and changes that have taken place in the five years since the last Party Congress in 2017.

Overview of the policy agenda of the 19th National Congress

In addition to appointing China’s top leadership, Party congresses also set general policy agendas and development goals for the following term. This policy direction is communicated through the Party Congress report, which is delivered by the Chairman while the congress is in session.

One of the most important development goals for the term of the 19th Party Congress was to “comprehensively build a moderately prosperous society” and “start a new journey of comprehensively building a modern socialist country”. The goal of reaching a “moderately prosperous society”, a concept first raised by Deng Xiaoping in 1979, was set to be reached by 2020 during the 16th Party Congress (October 8 to 14, 2002).

Achieving this goal is defined by a range of economic indicators laid out during the 16th, 17th, and 18th Party congresses. They include doubling China’s GDP and GDP per capita from 2010 to 2020, reaching an urbanization rate of 50 percent, a university enrollment rate of 20 percent, and an average disposable income per capita of urban residents of RMB 12,000 (US$1,686), as well as eradication of absolute poverty, among other factors.

In addition to reiterating the goal of achieving a moderately prosperous society by 2020, the 19th Party Congress laid out two phases of development for the country over the next 50 years, or two “centennial goals” to reach by the middle of this century. These goals are:

Phase one (2020 to 2035): Building on the foundation of a moderately prosperous society and basically achieving socialist modernization. The economic and development goals to achieve “socialist modernization” include:

- Greatly increasing China’s economic, scientific, and technological strength to rank among the top most innovative countries in the world

- Guaranteeing people’s equal participation and development rights

- Establishing a country, government, and society under the rule of law

- Significantly increasing the proportion of middle-income groups

- Significantly narrowing the gap in development and living standards between urban and rural areas and residents

- Fundamentally improving ecosystems and the environment

Phase two (2035 to 2050): Building on the foundation of modernity, build a prosperous, strong, democratic, culturally advanced, harmonious, and beautiful modern socialist country. No specific economic or development goals have been set for achieving this vision; instead, the focus is on more general improvement to society, governance, and prosperity, which include:

- Comprehensive improvement to the country’s material, political, spiritual, social civilization, and ecological civilization

- Modernization of the country’s governance system and capacity

- Basically achieving “common prosperity” for all people

The upcoming 20th Party Congress is expected to set similar short and long-term visions for China’s social, cultural, and economic development over the next half-century, and expand upon current growth and development policies.

Economic development since the 19th Party Congress

The economic goals of the 19th Party Congress have basically all been achieved in the subsequent five-year term. At the 100th Anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party on July 1, 2021, President Xi Jinping announced that China had succeeded in becoming a moderately prosperous society, making good on over three decades of development targets. Earlier that year, President Xi also announced that China had succeeded in eradicating absolute poverty in China, meaning that all citizens live on more than RMB 4,000 (US$562) by 2020 terms or US$2.8 per day by the World Bank’s standards.

Looking at the other economic indicators, China has also succeeded in reaching its GDP and GDP per capita targets set out during the 19th Party Congress. In 2020, China’s GDP exceeded RMB 101 trillion (approximately US$14.2 trillion today), more than doubling from the year 2010, which recorded a GDP of RMB 41 trillion (approximately US$5.8 trillion today). Meanwhile, GDP per capita reached US$10,500, more than doubling from US$4,628 ten years earlier.

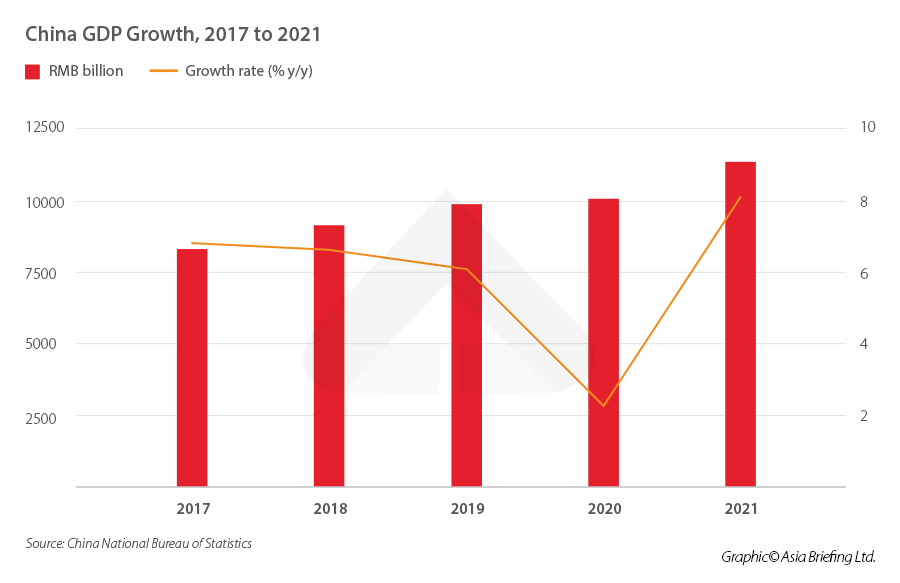

China’s economy has shown consistent and steady growth over the last five years, maintaining an annual average growth rate of almost 6 percent, despite the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic knocking the growth rate down to 2.3 percent in 2020. Throughout the pandemic, China’s economy has shown remarkable resilience and experienced a rebound in 2021 of 8.1 percent (due in part to the low base effect from 2020).

Overview of industry development

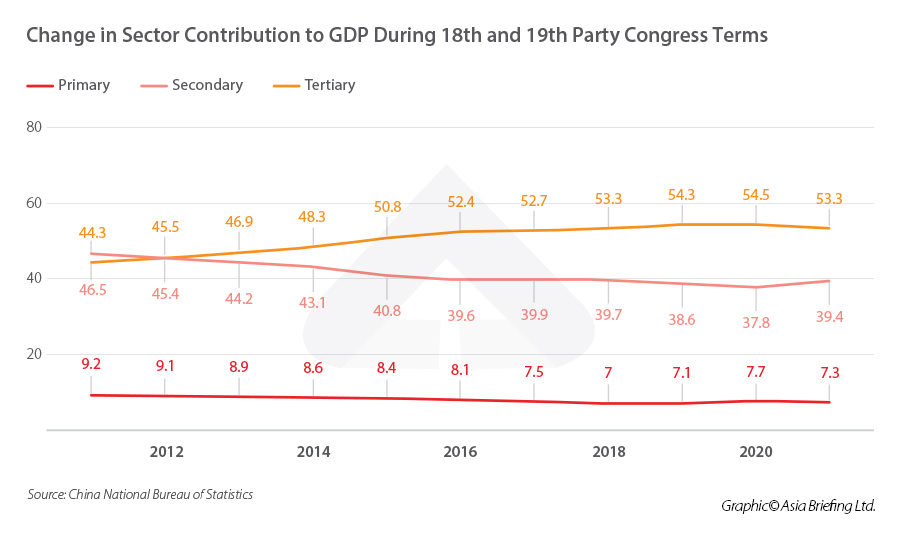

The largest proportion of China’s economy has been taken up by services ever since the tertiary sector overtook the secondary sector by proportion of GDP in 2012. Over the past five years, services have continued to grow while industry and agriculture have shrunk by the size of their economic contribution, slowly but surely. In 2017, services made up 52.7 percent of GDP. The proportion peaked in 2020, at 54.5 percent, and went back down to 53.3 percent in 2021. Meanwhile, manufacturing (secondary sector) and extraction of raw materials (primary sector) show the inverse trend – secondary sectors made up 39.9 percent of GDP in 2017, reached a low of 37.8 percent in 2020, and settled at 39.4 percent in 2021.

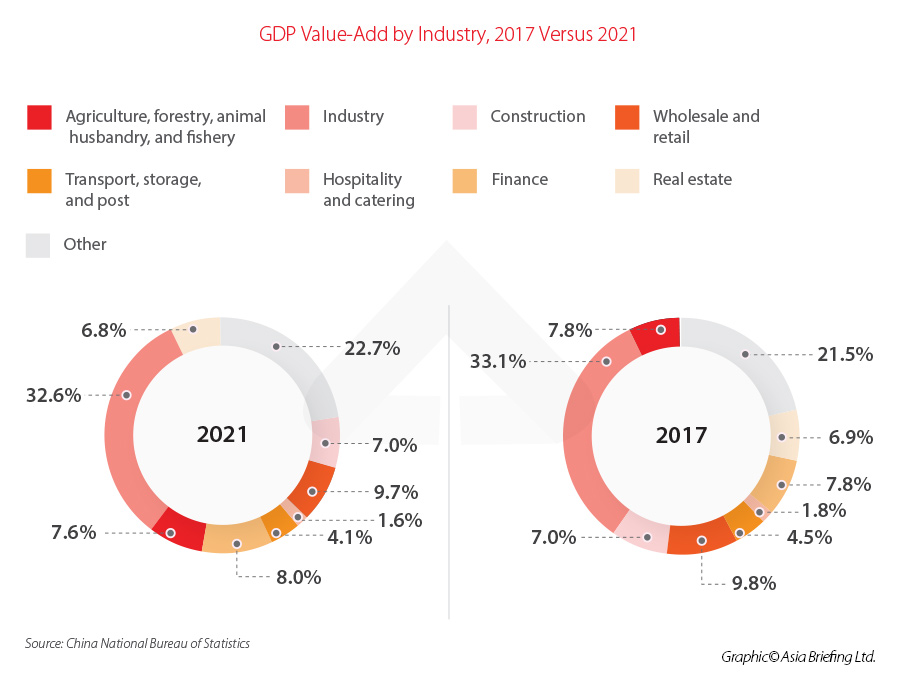

The change in the proportion of various industries to GDP over the last five years has been small, but nonetheless shows the same trajectory toward a service-led economy. Industries such as financial services have seen a small increase in GDP contribution, while agriculture and industry have seen a slight drop.

Technological development

China has made significant strides in technological development and innovation over the past five years. The field is seen as one of the most important for China to continue on the trajectory toward becoming a leading world economy and avoid the “middle-income trap”. With advanced technology and China can not only climb up the value chain and increase reliance on high-quality services but also upgrade its traditional industries, such as manufacturing and resource extraction.

The progress in technological development has been achieved through a concerted effort to incentivize high-end technology and innovation, through policies such as preferential tax schemes, talent schemes, government procurement schemes, investment drives, and more.

China’s technological development over the past five years is evident through a broad range of indicators, most prominently the growth in expenditure on technological and scientific R&D. Expenditure on R&D has grown both among private companies and the government, with total investment in R&D reaching RMB 2.8 trillion (US$392.1 billion) in 2021, an increase of around RMB 1 trillion (US$140.5 billion) from 2017.

Major policy developments and legislative changes

Further opening of Chinese markets to foreign investors

The last five years have seen further efforts by the Chinese government to open up new sectors for foreign investment and businesses. One of the key mechanisms for achieving this is the continued shortening of the Catalogue of Encouraged Industries for Foreign Investment.

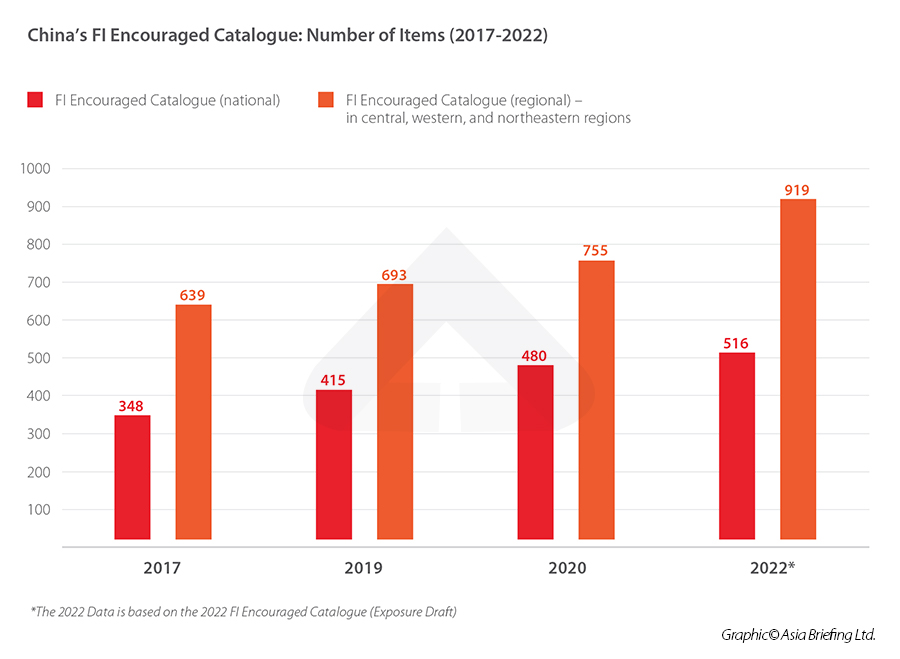

The catalogue of encouraged industries, which is updated annually, identifies industries where foreign direct investment (FDI) will be welcome and treated with favorable policies in China. It includes two sub-catalogues, one covering the entire country and one covering the central, western, and northeastern regions.

Over the past five years, the number of industries in both categories has steadily increased, from a total of 348 nationwide and 639 regional industries in 2017 to 480 nationwide and 755 regional industries in 2020. The draft 2022 catalogue has proposed to add 36 nationwide and 164 regional industries to the list.

China has also continued to expand on free trade and investment zones, areas that provide preferential policies, including tax incentives, for businesses in certain industries. These include:

- The Hainan Free Trade Port, first proposed in 2018 and formalized with the release of the Hainan Free Trade Port Law in 2020 (adopted in 2021).

- The Lingang New Area of the Shanghai Pilot Free Trade Zone (FTZ), established in 2019.

- A host of new cross-border e-commerce (CBEC) pilot zones, including 46 new zones announced in 2020.

- The Guangdong-Macao Intensive Cooperation Zone in Hengqin, Zhuhai, established in 2021.

- Expansion of the Qianhai Shenzhen-Hong Kong Modern Service Industry Cooperation Zone in Shenzhen from 15 square kilometers to 120 square kilometers to cover new areas including the Shekou Area of the Guangdong Free Trade Zone in 2021.

- The Huang-Bohai New Area in Yantai, Shandong, established in 2022.

Several of the above new areas and development zones offer preferential tax policies, such as a reduced 15 percent corporate income tax (CIT) rate for companies operating in key high-tech industries in the Lingang New Area.

Improving protection for foreign businesses through the Foreign Investment Law

The Foreign Investment Law (FIL), passed on March 15, 2019 and effective from January 1, 2020, sought to address common complaints from foreign businesses and governments with regard to market openness and fair treatment of foreign businesses. According to Premier Li Keqiang, the FIL “is designed to better protect and attract foreign investment through legislative means.”

The FIL achieves this in a number of ways. First, it explicitly bars Chinese joint venture partners from stealing intellectual property and commercial secrets from their foreign partners and prohibits government officials from using administrative measures to pursue forced technology transfers, making them criminally liable if they do so.

In addition, the law guarantees equal treatment for foreign investors when applying for licenses and participating in government procurement, and equal opportunity to participate in the formulation of standards.

Improving China’s business environment and reducing red tape

Another major drive to improve China’s business environment has been to improve the ease of doing business by reducing administrative burdens and streamlining government services.

The most concerted effort to achieve this has been through Premier Li Keqiang’s fangguanfu campaign. Fanggyuanfu is a short-hand term that roughly translates to streamlining administration, delegating powers to lower-level governments, and optimizing regulations and services. First launched in 2013, the fangguanfu campaign has seen significant progress over the last five years through decentralization, cuts to red tape, reductions in administrative penalties, and more.

Major developments under this campaign include reforms to the company chop regulations, including the introduction of an electronic chop and a crackdown on fraud by chop engraving companies, reductions in required licenses for various fields and industries, and reductions in administrative penalties for certain violations. It also includes the “separation of licenses” reform, which simplifies procedures for obtaining business licenses and operation permits.

In April 2022, the State Council issued an order to amend 14 and abolish six sets of administrative regulations across a wide range of industries in order to further cut red tape for companies and help stimulate market activity. The changes to the regulations, which took effect from May 1, 2022, cover foreign investment in the telecommunications industry, medical institutions, customs inspection, transport, internet access services, and many more.

The efforts to improve the regulatory environment for businesses have seen China move up from 78th place on the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Report in 2017 to 31st in 2020 (the report was discontinued in 2021).

The pandemic and China’s dynamic zero-COVID policy

A discussion of the business environment and economy in China is not complete without addressing the impact of COVID-19. China’s zero-COVID policy has maintained strict border controls for incoming passengers, which include a period of centralized hotel quarantine, as well as strict lockdowns, restrictions on movement and implementation of health codes, and regular mandatory testing.

The zero-COVID policy, also called the “dynamic clearing” policy, has succeeded in keeping China’s COVID-19 case numbers to some of the lowest of any country in the world. As of October 4, 2022, China had recorded a total of just 5,226 deaths from COVID-19, and a total of 251,620 confirmed symptomatic cases.

The hugely commendable success of China’s dynamic clearing policy in preventing a humanitarian catastrophe has not been without its sacrifices; one that has been felt particularly hard by foreign businesses. The strict quarantine requirements for inbound travelers have made it difficult for foreign businesses to send managerial and executive staff to China for office or factory visits, attract new foreign employees and even made it harder to retain the current foreign employees, many of whom are making the decision to leave China as a result.

Moreover, sporadic lockdowns throughout 2022 have forced major foreign-owned factories or contract manufacturers of multinationals such as Apple to suspend operations for periods of time.

China’s economic growth has also taken a considerable hit, with the World Bank’s latest GDP growth forecast for 2022 set at 2.8 percent.

The Chinese government has responded to the concerns regarding the impact of the dynamic clearing policy by issuing a range of support and stimulus measures, including assistance to vulnerable market entities, small businesses, and companies operating in at-risk industries, such as retail and catering, as well as tax and fee deferrals.

Moreover, the mandatory hotel quarantine and self-isolation period for inbound travelers has been gradually shortened from a maximum of 21 days in the early days of the pandemic (14 days of hotel quarantine plus a minimum of seven days of self-isolation and restricted movement), to the current 10 days (seven days of hotel quarantine plus three days of self-isolation). Pre-flight testing requirements have also been relaxed, and the number of flights bound for China has been steadily increasing.

On September 16, 2022, China’s Ministry of Culture and Tourism released an exposure draft of the Measures for Border Tourism Administration for public comment until September 29. The exposure draft encourages border areas in China to create designated tourist destinations, specifies that tourist groups can flexibly choose entry and exit ports, and remove preconditions, such as border travel approval and some entry and exit document requirements. Some analysts believe this is a positive sign that China will begin to reopen the country to foreign tourists, although only those part of tour groups would be allowed to visit the designated border tourist sites. Details regarding issues such as quarantine requirements upon arrival are yet to be released.

Common prosperity

One of the most important flagship economic and social policies to be released over the last few years in China is the common prosperity drive, which is likely to guide policymaking in China for the foreseeable future. First introduced by President Xi Jinping at the 10th meeting of the Central Committee for Financial and Economic Affairs in August 2021, the policy seeks to raise the incomes of low-income groups, promote fairness, balance regional development, and focus on people-centered growth. This included a pledge to “reasonably regulate excessively high incomes, and encourage high-income people and enterprises to return more to society.”

The common prosperity drive has already had a major impact on regulation and policy, with regulatory crackdowns on for-profit tutoring, video games, entertainment, and the use of algorithms to exploit gig workers.

In addition to regulatory campaigns such as these, common prosperity policies involve investments and incentives to address development and quality of life issues. For example, the Chinese government is embarking on a rural revitalization campaign to improve conditions in rural areas, encouraging industrial transfer to less-developed regions, and pursuing carbon neutrality.

Setting new climate targets and introducing carbon reduction policies

In a video address to the UN General Assembly on September 21, 2020, President Xi Jinping announced two core carbon emissions goals for China over the next half-century: reaching peak carbon emissions by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060. This announcement set in motion a new effort for the transition to a green economy and the release of a series of new policy documents and environmental action plans.

In the run-up to the COP26 summit in early November 2021, China released two key policy documents, further cementing its decarbonization commitments. These two documents form the basis of China’s “1+N” policy framework, where the “1” refer to the country’s guiding principles for reaching its climate goals, titled the Working Guidance for Carbon Dioxide Peaking and Carbon Neutrality in Full and Faithful Implementation of the New Development Philosophy, and the “N” stands for an unspecified number of auxiliary policy documents targeting specific industries, fields, and goals.

The first of the “1” documents, called the Action Plan for Reaching Carbon Dioxide Peak Before 2030 (“Action Plan”), was released along with the Working Guidance, and provides an extensive overview of the areas of China’s economy that will gradually be reduced or shifted to sustainable energy in order to slow the growth of high-carbon industries and areas of the economy.

Since then, a series of other “1” documents have been released, including the Guiding Opinions of the State Council on Accelerating the Establishment and Improvement of a Green, Low-carbon and Recycling Economic System, released in February 2022, and the Opinions on Financial Support for Reaching Peak Carbon Emissions and Carbon Neutrality released in May 2022. It has also continued to strengthen its requirements for ESG reporting.

Strengthening the cybersecurity, data, and personal information protection

One of the most significant changes in China’s regulatory environment over the last five years has been the development of the country’s cybersecurity and data and personal information protection regimes. The Cybersecurity Law (CSL), the foundation law for the protection of networks and data in China, came into effect in June 2017, a few months prior to the 19th Party Congress. Since then, China’s top cybersecurity authority, the Cybersecurity Administration of China (CAC), along with other government departments, have been actively building China’s data security and protection regime through the release of a series of landmark regulations.

The Data Security Law (DSL), which was passed in June 2021 and came into effect on September 1, 2021, stipulates how data is used, collected, developed, and protected in China. It emphasizes top-down coordination of data security implementation among local governments and differentiated fines based on the severity of violations and aims to further strengthen the current protection regime for the country’s fast-growing digital economy.

Meanwhile, the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL), which was adopted on August 20, 2021, and came into effect on November 1, 2021, is the first law in China specifically regulating the protection of personal information (PI). The PIPL adopts some concepts from Europe’s General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) with key differences in the scope of application, definitions, and legal basis for processing PI, among others.

In addition to these three pillars of the cybersecurity regulatory framework, China has also released a range of cybersecurity regulations, including regulations governing the cybersecurity of critical information infrastructure operators (CIIOs) and measures governing cybersecurity reviews, among others.

Looking ahead to the 20th Party Congress

China has made major strides in economic and social development, industry growth, and legislative and policy changes since the 19th Party Congress. Some of the most important milestones in China’s modern history have been achieved during this period, most notably the eradication of absolute poverty and the uplifting of the per capita GDP and social indicators to that of an upper-middle income country, per the designation of the World Bank.

Meanwhile, tightening regulations in areas such as technology and the internet suggest a maturing economy, with new and emerging industries subject to better standards and regulations. At the same time, easing unnecessary restrictions and requirements on businesses is helping to improve the business environment for both international and domestic businesses.

Looking toward the policy agenda of the 20th Party Congress, and thus the policy direction of the next five years, we expect common prosperity, the rebalancing of development between rural and urban regions, and the development of key industries that will help to move China up the value chain to take center stage. While it likely will not be the focus of the 20th Party Congress Report, the implications for foreign businesses will therefore be more incentives to participate in this rebalancing and development, through measures such as relocation to less-developed regions, expansion into fields that support China’s leveling up, and ensuring continued and steady growth of the economy.

Arendse Huld is an Editor for China Briefing, based in Shanghai, China.

This article was first published by China Briefing, which is produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm assists foreign investors throughout Asia from offices across the world, including in China, Hong Kong, Vietnam, Singapore, India, and Russia. Readers may write to info@dezshira.com for more support.