China’s dual circulation strategy (DCS) seeks to spur China’s domestic demand while simultaneously developing conditions to facilitate foreign investment and boost production for exports. The two-pronged strategy refers to the parallel emphasis on an “internal circulation” and an “international circulation”, and a shift towards becoming a demand and innovation-driven economy. The DCS is not an inwards-looking strategy, but the focus on tapping into China’s internal consumption patterns and domestic markets aims to buffer the impact of global economic headwinds and unpredictable external events on China’s economic and financial stability.

In May this year, when China had just caught its breath from the COVID-19 outbreak and western countries began to flounder, Chinese President Xi Jinping proposed a new economic model, the “dual circulation strategy” (DCS), at a Politburo meeting. Though the DCS would come to be more frequently invoked by the Chinese leadership in later meetings, it stirred up much discussion among China market watchers due to the absence of concrete details.

The Dual Circulation Strategy Explained

The “dual circulation” strategy (DCS) is a two-pronged development strategy that seeks to spur China’s domestic demand in addition to catering to export markets and will create conditions that allow domestic and foreign markets to boost each other. The strategy is slowly becoming the underlying policy refrain to accompany China’s actions to recoup loss of growth momentum due to the coronavirus outbreak. Some analysts, however, assume that this is a signal that China’s economy will look inward and reduce its exposure to the vagaries of the global economy.

Why China is Pushing DCS Now

Many analysts see China’s DCS as a quick and passive response to the unpredictability in global markets. In fact, the dual circulation strategy also follows China’s long-held goal of rebalancing its economy. In the 1980s, China’s former leader Deng Xiaoping first adopted the “reform and opening-up policy” and began implementing an export-oriented development strategy. As the tide of globalization grew in strength, China grabbed the many opportunities in its wake. Relying on the abundance of cheap Chinese labor and the country’s strong business ecosystem, lack of regulatory compliance, and low taxes and duties, China quickly became the “world’s factory” – the center of the world’s supply chain for many industries – and achieved what is now referred to in hallowed tones as the continuous rapid growth miracle of the Chinese economy.

The 2008 global financial crisis would soon expose the Chinese fast-growing economy to the fragility of the export-led economic model, prompting Chinese policymakers to rebalance growth towards cultivating and supplying domestic demand. In addition, there was an important realization – the export-oriented trade pattern where Chinese businesses import raw materials to process and then export to foreign markets – had locked China into the middle order of the global value chain.

To achieve sustainable growth and move beyond the limitations holding back its economic expansion, China began rolling out consistent economic reforms over the past decade, including supply-side structural reform in 2015 and its Made in China 2025 stratgey, which was announced in 2018. The ultimate goal has been to shift itself from being an “export and investment-led” economy to a “demand and innovation-driven” economy.

From 2006 to 2019, the trade-to-GDP ratio of China slid from 64.5% to 35.7%. However, while overall investment jumped, the portion of domestic private consumption only marginally arose, stabilizing at 38.8% of GDP in 2019 – barely higher than a decade earlier.

China’s economic transformation has not been smooth and faces many problems. But, recent dramatic changes in the global trade environment – promoting economic nationalism over a free market economy, for example – has made the cause more urgent for Beijing. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has additionally provoked global concerns on supply chain dependency, as different countries have been forced to rethink their reliance on other countries (especially in strategic industries, such as medical supplies and access to pharmaceutical raw ingredients), which will likely accelerate supply chain shifts out of China.

China’s economic transformation has not been smooth and faces many problems. But, recent dramatic changes in the global trade environment – promoting economic nationalism over a free market economy, for example – has made the cause more urgent for Beijing. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has additionally provoked global concerns on supply chain dependency, as different countries have been forced to rethink their reliance on other countries (especially in strategic industries, such as medical supplies and access to pharmaceutical raw ingredients), which will likely accelerate supply chain shifts out of China.

Growing concerns in the West about the impact of China’s integration into the global trade system are pushing countries, led by the US, but also increasingly by the European Union, Australia, and Japan, to weigh their trade ties with China. A general retreat from globalization among Western democracies could mean more limited market access to these countries for China. To make matters worse, COVID-19 and the shutdown measures to contain it, have plunged the global economy into the worst recession since World War II, adding to the woes of the global economic slowdown and resulting in a shrinking export market for China (with certain exceptions, such as in the case of medical supplies and vaccines).

In addition, the widening rift with the US, has triggered a decoupling of sorts between the worlds’ two biggest economies. The US crackdown on Chinese technology companies like Huawei is pushing China towards self-reliance on key technologies, such as semiconductor technology. Stephen Olson, a research fellow at the Hinrich Foundation, observes that “a new era in trade” is coming. “The trade landscape China will have to navigate henceforth will be considerably less benign than the one it traversed for the past two decades.” The DCS is also a signal that the Chinese leadership is prepared for the “new reality”.

China’s Next Steps Under DCS

The details of China’s dual circulation strategy have not yet been unveiled. What is certain, however, is its desired outcomes. In order to achieve a more sustainable long-term economic growth and hedge against the impact of external shocks, the world’s second largest economy will focus on building an unblocked “internal circulation” of domestic production, distribution, and consumption instead of over dependence on the “external circulation” of the global market. The disclaimer, of course, is that China will not simply forsake the export goose that once laid its golden eggs.

China has pushed domestic reforms for boosting private consumption for years, and this has been reignited by the impact of recent external ripples in the global economy. Key projects in this regard include faster reform of China’s land and residency (hukou) system, which is the ongoing urbanization program to turn millions of migrant workers into city dwellers. As well as building a highly consumer-driven economy, it would also involve materially tackling a yawning inequality gap that has weighed on local spending capacity by deepening the social safety net and via poverty alleviation campaigns.

China is already a “hyper-sized” consumer market with 1.4 billion people. Although its private consumption is lagging behind production amid unemployment and economic uncertainties due to COVID-19, its 400-million-strong middle class is steadily growing and offers extraordinary market potential. Under this trend, there will be opportunities in areas like health services and pension provision, as well as in the upgrading and digitalization of supply chain networks and the e-commerce industry.

Focusing on Strategic Sectors

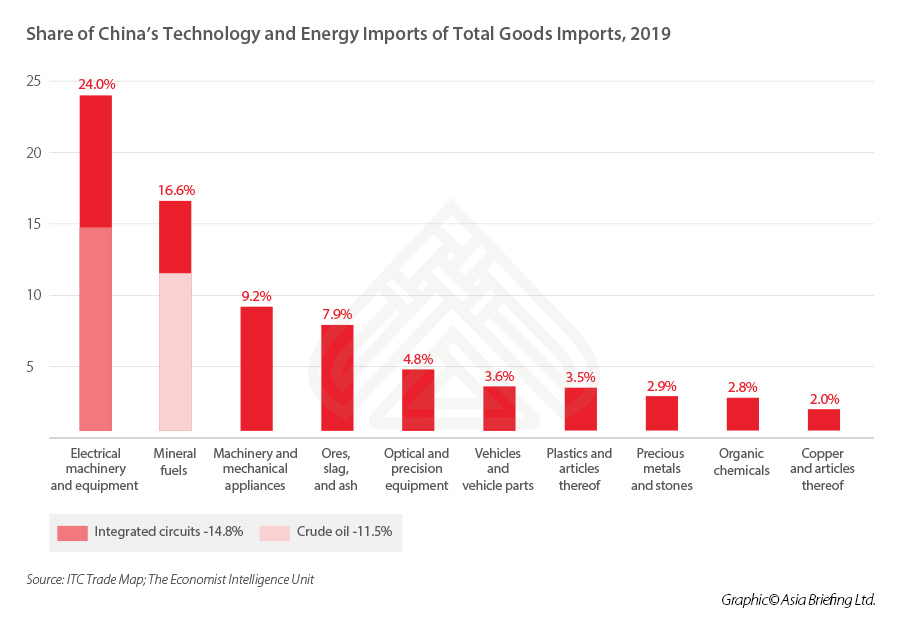

The other key element of DCS will be “reducing risks tied to import dependency”. As a report by The Economist Intelligence Unit analyzes, “technology, energy, and food will be the sector focus.” Tensions with the US have exposed the vulnerability of China’s supply chain – China relies on US$300 billion worth of imported semiconductors to meet over 85% of its domestic market demand. Thus, of all sectors, technology is poised to receive the most overt support for achieving self-sufficiency, with semiconductors or integrated circuits (ICs) getting the most attention. In fact, this August, China announced corporate income tax (CIT) breaks for IC and software companies.

In the energy sector, in 2019, almost 85% of China’s oil consumption and over 40% of gas consumption was derived from imports. Although China is less dependent on the US in this sector, compared with technology, recent geopolitical tensions have raised concerns about potential disruption to energy shipments. The key to avoiding this hidden danger is encouraging renewables and diversifying international relations in the energy sector, which could increasingly be pursued under the umbrella of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

In the food sector, it is forecasted by the Chinese Academy of Social Science that there could be a production shortfall of 25 million tons in wheat, corn, and rice by 2025 in China. The possible shortages in food supply would affect food prices and risk social stability. Due to rural labor shortages, lower agricultural productivity, and slow progress in rural land reform, China still relies heavily on imported foods, especially soybeans, imported seeds, and foreign planting and processing technology. Here, US farmers will enjoy some short-term opportunities, derived additionally from the agricultural product purchasing agreement set out under the Phase One trade deal. But, over the longer term, China will be keen to tap into a diversified group of suppliers, which should yield opportunities for farmers in Europe, Latin America, and those who are part of the BRI.

DCS and China’s Foreign Investment Environment

DCS and China’s Foreign Investment Environment

China’s DCS is currently vaguely defined, but it is expected to be fleshed out in more detail in the upcoming 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025). Given its outsized role in global trade, a minor shift in China’s trading patterns could elicit huge effects. Therefore, foreign investors engaging in this market should stay abreast of the latest developments and assess exposure to possible consequences. China likely sees this as a critical chance to deepen market-oriented reforms. This would address concerns on the allocation of production factors (land, labor, capital, and data) in the market, further gearing local producers to meet growing domestic demand and expand industrial output for both the domestic market and exports. For key sectors tied to national security, such as technology, energy, and agriculture sectors, China’s policymakers are expected to encourage more rapid foreign investment in high-end manufacturing and R&D besides supporting the diversification of global supply chains.

Considering factors, including China’s huge domestic market, comprehensive supply chain network, strong business ecosystem, rising labor costs, and aging population, many foreign investors are adopting “in China, for China” and “China plus one” strategies to tap into China’s market demand growth while also lowering costs, diversifying risks, and accessing new markets. For some investors, however, managing exposure to pressures in home markets will be the overwhelming challenge in the short term, but there is still great opportunity in China and Asia whose economies account for some of the strongest growth engines in the world.

Zoey Zhang is an Associate Editor at Dezan Shira & Associates, an AmCham China Corporate Partner Program member. The above article originally appeared here and was published in the AmCham China Quarterly magazine, 2020 Vol 3, which can be downloaded directly here.