In a country that according to Time magazine had 1,828 famines of one size or another between 108 BC and 1911 – and plenty more during the rest of the 20th century – it is perhaps unsurprising that the most common greeting in China is “Have you eaten?” While young urban-dwellers now eat well, the precariousness of existence for Chinese living on land that would only inconsistently provide them with enough to eat still looms large in the public consciousness, and government policy as well. But some observers both inside and outside China fear that the government is imprisoned by the country’s history, which is hobbling its ability to make rational and constructive decisions about maintaining the security of food supplies for its population.

The concept of food security is a slippery one that means different things to different people. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations has identified four pillars of food security: availability (meaning there is generally enough); access (individuals can get to it); utilization (people know how to eat healthily); and stability (minimum future risks to food availability and access). Most countries would struggle to meet all these criteria single-handedly, and China is no exception. Yet self-sufficiency remains nominally at the core of the nation’s food security policy.

Yong Gao, Director of Asia Corporate Engagement at Monsanto, believes this policy may be related to China’s recent history of the past couple hundred years, including foreign invasions and famine.

“The mindset is ‘Food production and supplies need to be controlled by my own hands,’” Gao said. “Even after the three-decade period of opening up, there is still a great fear of somebody else having control over food supplies. Whenever food imports go up, some people get worried.”

For many years, official policy was for the country to be 95 percent self-sufficient in grain production. Over the past couple of years, the government appears to have moved away from this commitment, talking instead about “moderate” grain imports and focusing on the quality of grain produced, rather than purely the quantity. This at least partly reflects the reality that China’s farmers are struggling to keep up with demand. Since 1960, grain consumption in China has risen fivefold to 500 million tons a year, and for most of that period production kept pace, with the country at times being a net grain exporter. But more recently, imports have risen sharply in a trend that appears difficult to reverse. If you add in soybeans, China struggles to be even 90 percent self-sufficient.

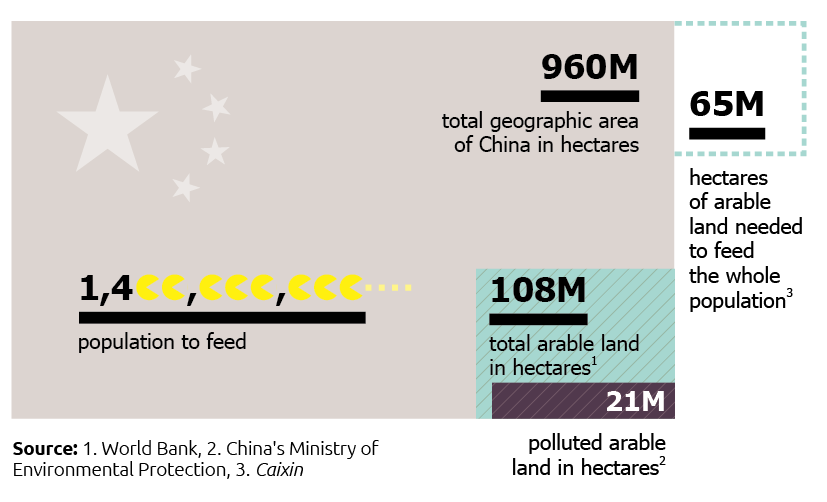

More telling is the impact of the low productivity of Chinese agriculture. According to State Council Development Research Center researcher Cheng Guoqiang, writing in Caixin, the country would need another 65 million hectares (160 million acres) – almost as big as the Dongbei region of China – to be able to produce the food, feed and oilseeds it currently imports. But arable land is in short supply in China, as is water. The truism widely bandied around is that China needs to feed roughly 20 percent of the world’s population with just 9 percent of the arable land and 6 percent of the water. As demand rises and arable land remains static, the choices for China, while challenging, are clear: increase productivity, increase imports, or both.

Getting more from the land

Since 1960, China has made impressive progress in ensuring its people have enough to eat. In meeting its United Nations Millennium Development Goals, for example, it halved the number of undernourished people in the country between 1990 and 2014 to 150 million people, or around 11 percent of the population, according to Food and Agriculture Organization statistics. But this progress has come at a high environmental cost, with the relentless application of fertilizer, pesticides and herbicides. In 2012, Chinese farmers used almost 650 kilograms of fertilizer on every hectare of land, compared with just 130 kilograms in the US, according to the World Bank. In late 2013, the government acknowledged that about 3.33 million hectares (8 million acres) of arable land – an area the size of Belgium – was too polluted to use. Overall about 19.4 percent of China’s total arable land is polluted to some degree.

While the chemical option has been exhausted, using better seeds with improved genetics and biotech traits could do a lot to increase productivity, said Gao. However, even though the government is promoting innovation in seed development in the domestic market, the seed industry for major crops remains a restricted area for foreign investment. Foreign firms are not allowed to do major crop seed business in China as independent parties. They can form joint ventures with a minority share to develop and market major crop conventional seeds, but are prohibited from breeding and marketing biotech seeds in China. This policy is in sharp contrast to other big agricultural countries like Brazil and Argentina where any company, regardless of ownership, is welcome to develop and market both conventional and biotech seeds. Wide adoption of improved seeds contributed to the rise of agricultural productivity in Brazil and Argentina in the past two decades, increasing the competitiveness of those countries’ farming sectors. Brazil has now become the biggest supplier of soybeans to China.

The animal feed sector, by contrast, is relatively open to foreign investment. Rather than becoming dominated by foreign companies, Chinese companies have thrived in the competitive environment to become some of the biggest global players in the industry. According to agribusiness media company WATT, four of the world’s top 10 feed producers are Chinese, including No. 2 New Hope Group, which now has several interests outside of China.

The situation with genetically modified, or biotech, food production in China is even more complicated. Despite heavy government investment, the only domestic biotech registrations in the past 10 years have been in cotton. For foreign investors, the sector is also prohibited, a situation that puzzles Philip Shull, Minister Counselor for Agricultural Affairs at the US Embassy in Beijing. He attributes the progress made so far in feeding the nation to past smart policies, which included embracing the most modern agricultural technology. So why has the Chinese government slowed or denied farmers’ access to the world’s best seeds with all the cost, yield and environmental benefits that they bring?

“Experts have told us it is a combination of wanting to help develop their own biotech seed industry, and fear that if Chinese farmers only used foreign seeds it could threaten China’s food security,” he said.

Plan B – buying from abroad

Even in the best of situations, China will never be able to produce all its own food. The question is more of what to import and how.

China isn’t alone in having to make these calculations – many countries, notably Japan and South Korea, need to secure most of their food from overseas. But China is far bigger than those two countries put together, and the impact of China’s increasing appetite on global food supplies is of increasing concern.

In an article published last year entitled “Can The World Feed China?,” Earth Policy Institute President Lester Brown ominously asked if China’s increasing food requirements would lead to higher global food prices and political unrest. China’s Ministry of Agriculture dismissed these concerns, but unless domestic farmers can increase productivity quickly, it seems food on Chinese plates will increasingly be produced overseas.

This has already happened with soybeans, where the government has largely thrown in the towel in terms of trying to satiate demand domestically. China now imports around 85 percent of its soybean requirements, mostly biotech varieties from North and South America. A little over 40 percent comes from the US, making it one of the most valuable US exports to China. Reliance on outsiders for genetically modified versions of a fundamental part of Chinese cuisine might have caused more hand-wringing were it not for the fact that the majority of imported soybeans are used for crushing into oils for cooking and food processing, and meal for livestock feed.

But now attention is turning to the other grains, imports for some of which rose sharply over the past year.

“China should have no problem with self-sufficiency in rice and wheat – it is internationally competitive in these crops,” said Juhui Huang, Senior Director of Government Relations and Chief Representative of the Archer Daniels Midland Beijing Office. But for corn, the production cost is around 40 percent higher – and the market price two to three times higher – than in the US because of a government-set floor price and a complex tariff system that discourages imports. This resulted in a corn surplus in 2014, although Huang believes the regulatory system around corn is unsustainable. “Longer term, corn may follow the same pattern as soybeans, as China understands the limits of its resources, he said.”

With China’s engagement with the international grain trade increasing, so are the rumblings of discontent. New varieties of biotech corn need to be approved by the major importing countries before they can be commercialized. At 60 percent of the market for soybeans, China’s demand makes its approval essential for the rollout of new varieties, but that approval has become increasingly difficult and slow in coming.

“China’s biotech approval process has gone from being slow but relatively predictable to slower, less predictable and resulting in non-science-based decisions,” according to Working Together to Improve Chinese Agricultural Sustainability, a paper released by AmCham China in February. “Though China is a major buyer of US commodities, the arbitrary nature of its approval system deprives Chinese consumers of the benefits of new technology-derived agricultural products. Additionally, the approval system weakens China’s ability to secure stable sources of grain and ease inflationary pressure” because China’s prolonged import approvals result in delayed adoption of new technology and innovations by the farmers in export markets such as US, Brazil, Argentina and Canada.

At a bilateral meeting last December between the US and China in Chicago, China announced that it was approving two more types of genetically modified soybeans, as well as a biotech corn variety, but the market disruptions are unlikely to go away quickly.

From the source

In another sign that, tacitly at least, the Chinese authorities acknowledge the necessity of imports, Chinese companies have been buying up chunks of the global supply chain for agriculture products.

State-owned China National Cereals, Oils and Foodstuffs Corporation, more commonly known as COFCO, has been at the forefront of this drive, last year paying around $3 billion for controlling stakes in Hong Kong-based trading house Nobel Group and Dutch agricultural products company Nidera. The deals give COFCO assets in major grain- and vegetable oil-producing regions such as Brazil, Argentina, Indonesia and the Black Sea, as well as reduce its reliance on the four major global commodity traders. COFCO Chairman Frank Ning said his company would “set up a stable grain corridor between the largest global grain-growing origins and the biggest global emerging market.” COFCO’s activities come during the apparent collapse of a deal signed in 2012 whereby China provided around $3 billion in loans and goods to Ukraine that would be paid back in grain during subsequent years. The nature of the deal is similar to how China secures access to energy and mineral resources around the world, but political instability in Ukraine and conflict with neighboring Russia have greatly reduced the chances of this agreement being honored.

While state-led initiatives are having mixed results, private companies have also been expanding their influence. Bright Food has been aggressively expanding overseas, buying Manassen and Mundella Foods in Australia and Synlait Milk in New Zealand. By far the biggest deal was Shuanghui’s $4.7 billion purchase of pork producer Smithfield in 2013, which still stands as the largest acquisition of a US company by a Chinese one.

In many of these purchases, the goal was getting control of the asset while retaining the local management, a strategy that Michael Boddington, Managing Director of Asian Agribusiness Consulting, believes best serves China’s long-term strategy.

“You’re seeing a lot of strategic investments for China’s requirements,” said Boddington. “These companies that are making large investments, you’ve got to think they have a thorough understanding of the government’s goals to secure food and are viewing these opportunities in the same way the government is seeing the requirements.”

Playing catch-up

Slow development of the technologies that could boost domestic production combined with reluctance to engage wholeheartedly with the global grain trade mean Chinese consumers will likely continue to pay above market prices for their food and suffer chronic environmental degradation. But with demand yet to top out, it’s likely that something in the current policy will crack from the pressure, unless a natural disaster intervenes first.

“Under normal conditions, production will likely be stable and slightly increase over time,” said Gao of Monsanto. “But if there was some kind of natural disaster or crisis, it could mean that sourcing for imports of a certain grain aren’t enough to cover the shortfall in the short term. It could be bugs that are resistant or some kind of widespread crop disease, and then the threat could elevate.”

In the meantime, China’s agricultural sector has its work cut out improving competitiveness in an increasingly complicated and misunderstood industry. Shull at the US Embassy finds it ironic that school children around the world learn the names of pioneering industrialists such as Henry Ford, but not Norman Borlaug, so-called father of the Green Revolution. He cites the tenfold increase in US corn yields between 1940 and 2010 as just one example of how massive increases in productivity have allowed food production to keep pace with population gains.

“The fact is that agriculture and food processing have become extremely high-tech. Unfortunately, rapid urbanization has led to a sharp decline in general understanding of where our food comes from and how it gets to the store,” Shull said. “People readily accept complexity of computers or medicines, yet because food looks simple and we eat it every day, everyone thinks they understand it.”

Graham Norris is AmCham China’s Senior Director of Communications.